MAXINE AT EIGHTY

My wife, Maxine Apergis was born during the second year of the Second World War, inHolbrook, Suffolk, into a medical family. She grew up in London and was educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College; in her last year at school she won the Concerto Class at the Cheltenham Competitive Music Festival. She went onto study music at the Reid School of Music at Edinburgh University but left at the end of her first year because the course was too academic and didn’t contain enough ‘real’music.

In 1965 we were married went to live in Kenya, where Richard our eldest son was born. Son Guy and daughter Claire were born in England after our return to Britain where we bought a house in Willingham, Cambridgeshire, where Maxine met Jim Potter, a horn player who had played in the National Youth Orchestra, and who persuaded her to take up playing again as he needed an accompanist.

C

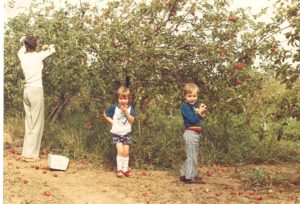

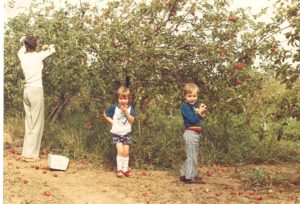

Claire & Guy in Willingham and with Maxine in the orchard

Claire & Guy in Willingham and with Maxine in the orchard

It was when we moved Gaborone, Botswana in 1986 that her musical career really took off. In Gaborone, she met and worked with David Slater, “Mr Music, Botswana”, who taught at Maru-a-Pula, the leading secondary school in the country: he also conducted the Gaborone Orchestra and ran several choirs. Maxine took lessons with David and he persuaded her to study for the Associated Board Teaching Diploma, which she obtained in 1988. Aside from her teaching, she gave solo piano concerts as well as accompanying the Gaborone Singers for their Christmas concert on Radio Botswana, individual singers, instrumentalists, and theatre performances given by the Capital Players (the local amateur theatre group).

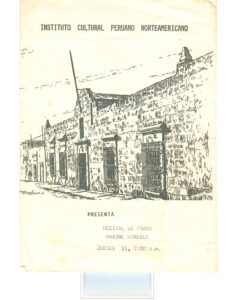

When we moved to Arequipa, Perú in the 1986, Maxine was invited to teach at the Dunker Lavalle Music School in the city. She also gave private piano lessons: one former pupil is now conductor of The Arequipa’s Symphony Orchestra; a second is now a leading recorder player in South America. Maxine’s career as a soloist and accompanist burgeoned in Peru, where she gave solo recitals around the country for the American, French and German cultural organisations, for the British Council and in aid of a Catholic children’s charity. She also accompanied visiting international instrumentalists, including an exciting evening in Cuzco with the French Cellist René Benedetti, when the French Consul insisted that she carry his pistol!

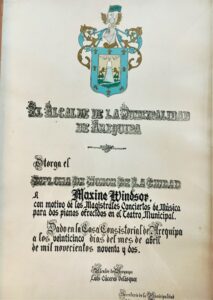

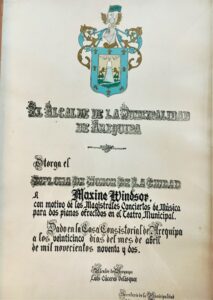

Maxine took masterclasses with Dr H. Delgado, a former pupil of Claudio Arrau, and was invited with her colleague Hugo Cueto to give a two-piano concert to mark the 450th anniversary of the foundation of the City of Arequipa. The City awarded her the Diploma de Honor, equivalent to the freedom of the city, for her services to music in Perú.

The 450th Anniversary Concert Diploma de Honor

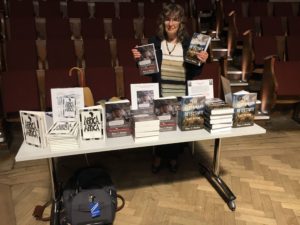

In 1992 the family returned to Britain and we settled in Dumfries, When she arrived in the town Maxine began setting up a “permanent career” for herself and since that date she has taught more than 300 pupils from the ages of under 8 to over 80! She has accompanied more than 500 singers and instrumentalists in concerts, examinations, or festivals. She nurtured the talents of the young Nickie Spence and accompanied him at his first professional engagement. Alex McQuiston was still at school when she accompanied this fine young cellist and she accompanied him while at University and into his first graduate concerts. Claudia Wood was another young Dumfries singer who benefited from Maxine’s care. She also took part in the musical life of the community: years. She joined the Music Club, was soon on the committee and for two years was President.

When the Dumfries and District Competitive Musical Festival Association fell on hard times we signed up as trustees and help nurse the society back into financial health. Together with Doreen Jaap, Maxine revitalized the classical music section of the Festival and in one year they had more than 150 entries in the different classes; The Dumfries Musical Theatre Company, The Guild of Players, Male Voice Choir, Balliol Consort and Solway Symfonia have all used her services as accompanist. With John Chaman (clarinet) and the sadly now deceased Susan Beeby (cello), Maxine formed the Caerlaverock Trio which gave concerts round the region, especially for Dumfries Arts Festival.

Today, Maxine plays in informal groups with the leading musicians in the region. For almost 30 years she has given pleasure and provided inspiration as well as tuition to young performers, several of whom have gone on to become professional musicians. On the occasion of her eightieth birthday, Dumfries and Galloway Life said MANY HAPPY RETURNS MAXINE, and “THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC”..

Feeding the baby leopard

Claire & Guy in Willingham and with Maxine in the orchard

Claire & Guy in Willingham and with Maxine in the orchard